JANUARY 12, 2013

Compounding - in life and in investments

While the better-skilled people or products would come out ahead, luck plays a part too

BY TEH HOOI LING

A world where the winner takes most Singapore stocks, rank and size on a logarithmic scale

WE all know about the power of compounding in investments. Let's say A, B and C start with $10,000 each. If A can make her $10,000 grow by 15 per cent a year, and then redeploy the bigger pot to grow by another 15 per cent the next year, by the end of 30 years, that $10,000 would have grown to $662,000.

Constrast that with C, who manages to grow her pot by just 5 per cent a year. By the end of 30 years, that $10,000 would have grown to only $43,000 - that's just 6 per cent of A's, even though they started off at the same level.

As with compounding that occurs in investing, in life too the effect of compounding plays a big part.

The compounding in life can take place as a result of our decisions, or it can be due to circumstances beyond our control. In other words, luck plays a role and, over time, the small break one gets because of luck is compounded over time to result in a wide gap between two persons who may start off at the same positions.

According to Michael Maubossin, author of The Success Equation - Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing, the process of social influence and cumulative advantage frequently generates a distribution that is best described by a power law.

According to him, an astonishingly diverse range of socially driven phenomena follow power laws, including the rank and number of books sales, the rank and frequency of citations for scientific papers, the rank and number of deaths in acts of terrorism, and the rank and deaths in war.

The example which he plotted in the book is the rank of US cities and the population size. The power law demonstrates the phenomenon of success attracts success. It's a winner takes all model. A popular singer gets more popular because of more radio time, and her fans will influence their friends to become fans.

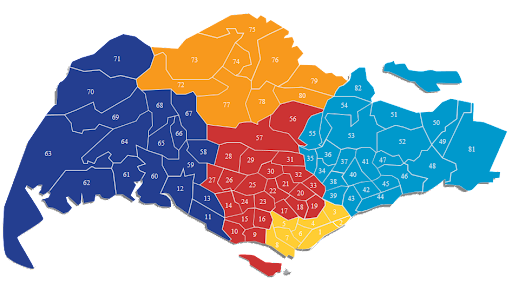

One of the key features of distributions that follow a power law is that there are very few large values and lots of small values. This sentence set me thinking. That sort of describes the distribution of stocks listed on the Singapore Exchange - there are a few very big companies, and there are a lot of small companies.

Do the ranks and size of stocks trading on SGX follow the power law? Well, guess what? They do! See Chart 1.

In power law distributions, the idea of an "average" has no meaning.

Our life trajectories, as in a lot of processes that involve social influence, are path dependent.

Robert K Merton, a renowned sociologist who taught at Columbia University, called this the Matthew effect, after a verse in the Gospel of St Matthew: "For whoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance; but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath."

Consider the case of two graduate students of equal ability applying for a faculty position. Say by chance one is hired by an Ivy League university and the other gets a job at a less prestigious college. The professor at the Ivy League school may find herself with better graduate students, less teaching responsibility, superior faculty peers, and more money for research than her peer. Those advantages would lead to more academic papers, citations, and professional accolades. This accumulated edge would suggest that, at the time of retirement, one professor was more capable than the other.

But the Matthew effect explains how two people can start in nearly the same place and end up worlds apart. In these kinds of systems, initial conditions matter. And as time goes on, they matter more and more, explains Mr Mauboussin. A number of mechanisms are responsible for this phenomenon. A simple one is known as preferential attachment. Mr Mauboussin gives the example of a new website. To make your website popular, you'd want to link your website to sites that already have lots of connections to other sites, including Google and Wikipedia, rather than sites with few connections.

So in order to get ahead, you have a preference for attaching to sites that are already well known and frequently visited. This behaviour causes positive feedback for the already popular sites: The more connections it already has, the more new connections it will get. Less popular sites will fade into obscurity. Initial differences, even modest ones, are amplified over time.

Mr Mauboussin illustrates this with a jar with five types of marbles. Initially, there are 15 marbles in the jar: five red, four black, three yellow, 2 green and one blue. Here's the experiment. Draw one marble, if it is black, you return the marble to the jar, and you add one black marble to it. Now there are five black marbles. Repeat the process, randomly pick a marble, replace it, and add one of the same colour. Do this with a number of jars. Most times, the red marbles will come out ahead. Sometimes yellow. On rare ocassions - the distinct long shot - blue will get ahead.

Mr Mauboussin uses the different colour marbles as proxy for skills. On average, the better-skilled people, the better products, would come out ahead. But sometimes, in some circumstances, luck gives a person or a product a break and that made the difference - like the rare ocassions when the blue marble ran away with the game.

Critical points and phase transitions are also crucial for the Matthew effect. A phase transition occurs when a small incremental change leads to a large-scale effect. This is also known as the tipping point, as talked about by Malcolm Gladwell in his book of that same name.

Mr Mauboussin cites the case of Oberlin College. When US News first ranked colleges in early 1980s, it was ranked fifth among liberal arts colleges, in large part because of its strong reputation. But a few years later, US News changed the method it used to rank colleges. It lowered the importance given to the assessments by presidents, provosts and admissions offcers. Oberlin dropped out of the top 10. The school's ranking continued to sink and, within a decade, it was close to falling out of the top 25. That's the negative effect of social influence at work.

So what's the takeaway? Well, it suggests that in anything that involves social influence, it is very difficult to predict the outcome. Many people in areas where social influence operates are often paid for good luck. And if you are in a good place in life now, it could mean that you've got a lucky break early in life. So be humble.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote